This past week, nilenso interviewed a German fellow for a software development position. As part of the routine of meeting a new stranger in this city, a variation of “Why do you live in Bangalore?” passed between us. My answer to this question is complex and usually varies based on the tone and implied subtext with which the question is asked. My immediate reasons are somewhat boring. My job is here and I like my job. My friends are here and I like my friends. The weather is pleasant.

Beyond that, however, I have wanted to capture my answer to this question in a way that could be conveyed clearly, immediately, convincingly. The complexity of the answer derives from the juxtaposition of Bangalore’s past 15 years of growth against her next 15 years. I am quite convinced that anyone who knows Bangalore today only needs to think creatively about the latter half, since they are intimately familiar with the former. Hence, I plan to commission artwork (as I am no artist) which captures Bangalore’s upcoming progress. This document is an open description which I intend to use for this purpose: Anticipate Bangalore 2030 and provoke both conversation and action.

Just Suppose We Juxtapose

Every feature of this commissioned artwork falls into one of two categories: The first is a quality native Bangaloreans say the city is losing or has already lost. The second is a feature which many established cities actually lack but are retrofitting onto legacy architecture and infrastructure. Features lacking in most major metropolises can be contrasted to Bangalore’s present state not only to highlight where the city is going but to emphasize how Bangalore might leapfrog the models of other cities in 2015 to push toward a more effective society based, at least in part, on the pressure caused by its failing infrastructure.

Both forms of duality will become clearer by way of example, but this point cannot be stressed enough: Backpressure is a good thing. Bangalore is positioned to lead by quiet example in a very short period of time, given a concentrated effort. By way of counterexample, Chicago (the last city I lived in) has no garbage crisis. It’s unlikely it ever will. Without backpressure from the system of waste disposal reaching the citizens, it will be decades (perhaps a generation) before Chicago sees a distinct shift in behaviour within every household.

Why Bangalore?

Bangalore is in a position few other cities are in at the moment. It is changing quickly. Very quickly. It is in a small flux from week to week alone and it undergoes drastic changes every few months. If I visit my family and Canada and return a month later, entire streets are sometimes unrecognizable. Some of this change is moving in the opposite direction this document proposes as the city becomes increasingly industrialized, commercialized, and modern. However, much of that change is absolutely necessary if we are to envision Bangalore as a New World City. Its metro population is that of New York and London; by 2030 it will have outstripped them. Its new workforce is largely post-industrial technology firms and supporting industries. It’s not hard to imagine Bangalore as a city of the future.

Bangalore is also a cheat. The weather here supports year-round bicycling and yet much of the flora remains tropical. Choosing Bangalore when fantasizing about cities of the future circumvents a multitude of problems. The ground does not freeze. It is far from the ocean and does not suffer many natural disasters. It seems likely that many of Bangalore’s immigrating technology workers choose it for this very reason, though, which in some ways validates choosing it for this thought experiment.

Lastly, Bangalore supports an array of cultures and (so far) does so in a way that they do not seem to melt together. New York is metropolitan but it doesn’t always feel that way. Londoners feel like Londoners. Bangalore’s masjids, bars, temples, restaurants, churches, mansions, slums, government offices, parks… they are a bizarre blend of activity that I have yet to experience in any other city. If infrastructural and behavioural change can work in Bangalore, it can work anywhere.

Juxtapose: Traffic

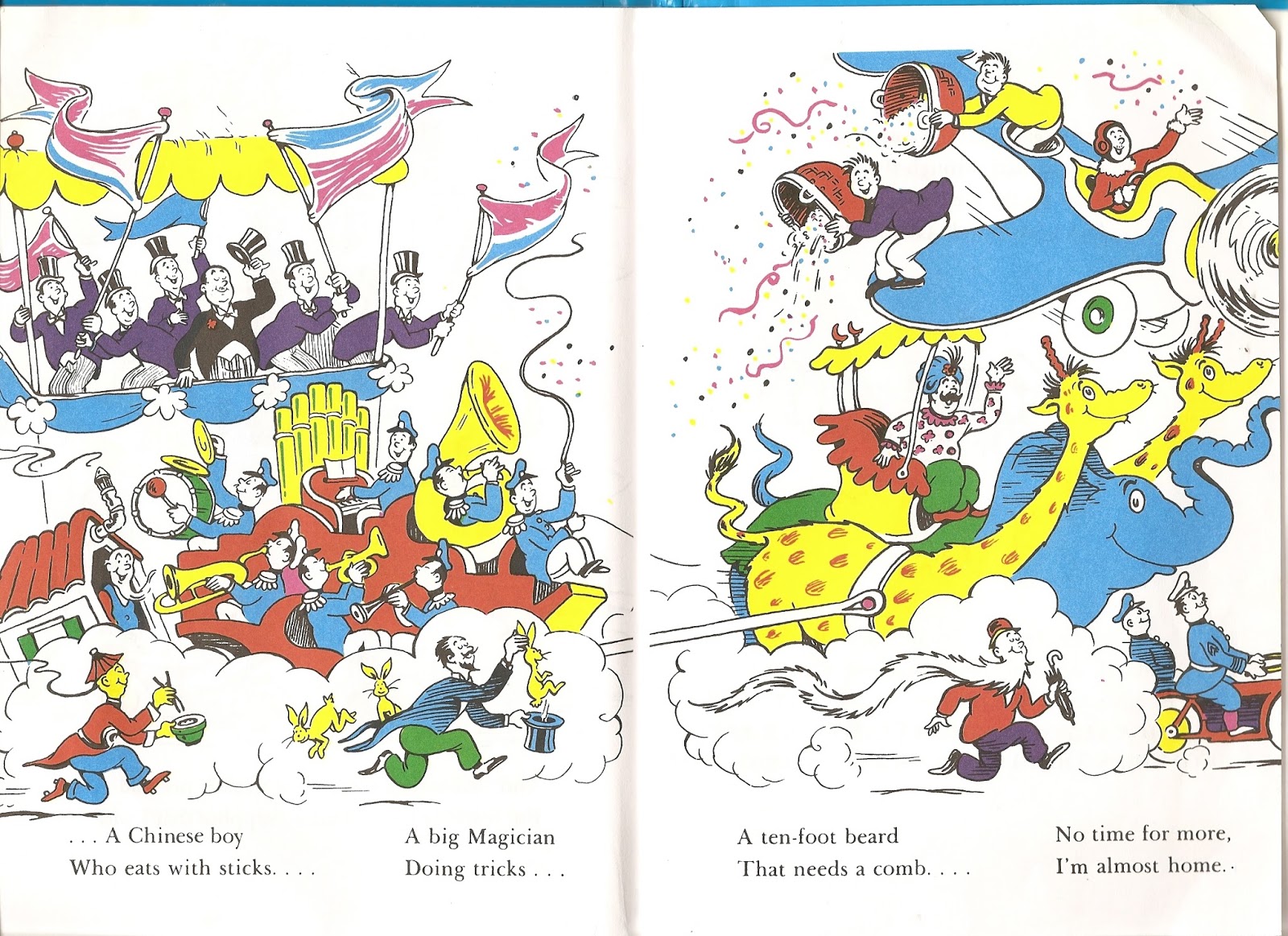

Bangalore’s traffic is a mess. Once a sleepy city full of retirees, old streets are now packed with trucks, buses, single-occupant cars, 2-wheelers, bicycles… and even the odd bullock cart. No one enjoys driving in Bangalore and even getting around as a passenger can feel stressful. Because the arteries of the city are clogged with every shape and size of vehicle, drivers get frustrated and address each other with incessant honking. Air and noise pollution choke the streets. A Bangalore commute often feels like traveling on a fantastic version of Mulberry Street.

The Metro: The Namma Metro is nearer and nearer to completion every day. Some of my friends already use it for a portion of their commute, despite the fact that the entire length of the metro’s journey is walkable at the moment. The project seems forever-delayed, but a vision of Bangalore 2030 features the metro as its centrepiece. As long as the memory of Bangalore’s traffic in 2015 is fresh in everyone’s minds, there should be no shortage of public support to continue expanding the metro to new neighbourhoods. Electric feeder buses don’t exist in Bangalore now, but are not hard to imagine as a staple form of transportation by 2030.

Bicycles: Copenhagen and Amsterdam were not always the cyclist’s paradises they are perceived to be now. In many cities, the convenience of the car easily trumps the desire for most to choose a bicycle, even for those convinced of the environmental, health, and resource benefits. That line of thinking is hard to follow in Bangalore, though. At the moment, it’s often faster to get across the city by bicycle than it is by car, simply due to agility. Bangalore is infinitely bicycle-able: The traffic is safe, due to its slowness. The weather is perfect 10 months of the year. The roads could be better, but they are constantly improving. There are very few gradients.

Bangalore has seen a small surge in its bicycle interest among the middle class. Shops like BumsOnTheSaddle, The Specialized Store, Crankmeister, and ProCycle have popped up in recent years. A bicycle culture can’t be subsidized by the government and won’t materialize apropos of nothing. But the sooner Bangalore’s bicycle renaissance occurs, the sooner it will snowball into dedicated bicycle infrastructure whenever a new road is paved.

Fragile, Indian-made bicycles and/or those with century-old designs (Hero, Atlas) still comprise the entirety of the bicycle market for Bangalore’s lower economic classes. These still fall in the Rs. 5000 to Rs. 10,000 price range… which isn’t actually that affordable. Simple, reliable, single-speed steel-frame bicycles could be produced in India at that price.

Electric, Automated Taxis & Rickshaws: Though not as revolutionary as clean public transportation or a confluence of Bangalore’s two bicycle cultures into the middle classes, electric and autonomous vehicles do seem the most cartoonishly futuristic. They’re not. Self-driving cars are on the streets in the US and Europe. Fully-electric cars have been a reality in India for 20 years and it’s not hard to imagine that within a few years the Revas and E2Os will keep the company of Bangalore’s first Teslas. With the advent of just-in-time taxi services, the future of roads in any city (not only Bangalore) is obvious. Fully electric cabs can already be seen on Bangalore streets. On the streets where cars are still permitted in the Bangalore of 2030, it seems likely that many cars will carry 4 or 5 passengers but no driver. Rickshaws inhabit a different slice of the economy and may still have human operators in 2030 but the polluting two-stroke engines of today will be seen as legacy. Electric rickshaws and electric bicycle rickshaws are already common in Delhi.

While an electric, autonomous vehicle is unlikely to generate much noise pollution, I can’t help but imagine that as awareness of the damage noise pollution does (to humans and animals both) goes up, clear “NO HONKING” signs will become the norm.

Work From Home. The late-90s dream of telecommuting has panned out differently for everyone who dreamt it. Some of us can’t focus at home. Some jobs still require interacting with the physical world. But for many (including about half the nilenso office) remote and distributed are the new default. I can’t actually envision how one would capture this in an art piece about Bangalore 2030, but it’s a reality, all the same.

Juxtapose: The Garbage Crisis

Thankfully, the citizens of Bangalore’s surrounding villages have started to fight back against the dumping of garbage in their homes. The backpressure of their resistance causes Bangalore’s streets to fill with Garbage. This is fantastic.

It might seem odd to think of Bangalore’s garbage crisis as a good thing, but if the infrastructure existed to truck the trash of 8.5 million people far enough away from the city that no one needed to think about it… then no one would think about it. As it stands, the truth of our waste is in our faces. Every day, on every street.

Compost: The more I think about compost, the more confused I am about the fact that it isn’t the default option for wet waste in every city of the world. But within Bangalore, it is obviously the right choice, since it is the only option the government currently supports. Wet waste, disposed every day, goes to a city-wide composting facility as long as it is not stored in a plastic bag. More adventurous citizens can compost easily at home.

“Dry Waste”: Garbage workers pick up “dry waste” (recyclables) twice a week. Thanks to a massive labour force, Bangalore’s recyclable waste is actually sorted at recycling centres… even though this should be the responsibility of every citizen. Composting and recycling is the government-requested (and desperately needed) default in 2015. In addition to basic waste segregation, it’s not unlikely that “NO FIRES” signs will become commonplace as lighting roadside garbage fires becomes illegal.

Recycling: True recycling in 2030 will mean recyclables are separated at the source. Every home will wash and segregate plastic, metal, and glass from e-waste, paper, and cloth. The best implementation of this system I have ever seen was in Tokyo, where my AirBnb instructions explained that plastics were to be sorted into three categories before providing them for pickup. As long as there is a garbage crisis, there is the perfect opportunity to teach the public about proper recycling in a tangible way that directly affects their personal comfort.

Juxtapose: Power Cuts

Bangalore experiences common power cuts. Some are very intentional and continue year-round. Others are based on a lack of water in the dams which feed Bangalore’s primarily hydro electricity supply. For a city with a growing economy, this has meant diesel generators for large businesses and battery backups for SMBs like nilenso. Running tiny power plants in every major business contributes to Bangalore’s asthma-inducing air pollution.

Solar and battery: Thanks to the emergence of lithium-ion batteries, the batteries of 2015 should quickly become relics. Currently, nilenso operates on some rather hideous batteries which require us to fill them with water periodically. They occasionally spill acid on the floor. They’re huge. But the fact is: They exist. Out of necessity, businesses and homes in Bangalore already have the kind of battery backup Tesla intends to sell to every American. Whether Bangalore becomes the biggest Tesla Powerwall customer by 2030 or not, some form of lithium battery will overtake the existing market. Solar panels are increasingly affordable and not only offer freedom from the grid during power cuts but would provide homes and businesses with resilient, distributed electricity during floods or other disasters (as Chennai is currently experiencing). A Bangalore of 2030 has a cityscape of buildings blanketed in solar panels.

Juxtapose: The Mud of the Monsoon

While we’re on the topic of floods, we can address Bangalore’s annual battle with the monsoon. The slightest rain seems to bring the city to a halt. Streets are somehow instantly clogged with both water and traffic and the power goes out in most neighbourhoods. The latter would be taken care of by building-independent power sources. The former, by proper infrastructure.

As of today, sanitary sewage and storm water are both dealt with using semi-covered and uncovered “drains”. When a street floods, the sanitary sewers are overburdened and waste water (including human faeces) is ejected into the street, endangering citizens’ health.

Storm sewers: Bangalore needs a massive storm sewer system, akin to the Ninja Turtles’ portrayal of the storm sewers in New York: Underground, walkable for maintenance, and completely separate from sanitary sewers. Bangalore gets plenty of rain. Rather than the present nuisance, it could wash a dusty city clean, restock water tables, and irrigate nearby farmland.

Sanitary sewers: New sanitary sewers between now and 2030 need to be built underground and completely covered. Disposal will be to a proper waste water treatment plant or — preferably — to a more future-focused human waste composting plant. An image of separate storm and sanitary sewers is easy enough to imagine, though the specifics of where they go afterward is a bit more difficult to portray in a painting.

Public toilets: After a recent trip to Hyderabad, I was amazed to see the heavy usage of public toilets on most major streets. This is fantastic for a number of reasons. A government-installed public toilet is a perfect opportunity to dig an underground sewer where one might not yet exist. It’s also an opportunity to raise awareness about where the local sewage is draining — and where it should drain. I also traveled to Vancouver recently and was pleasantly surprised to find public toilets available in every park, where children and the elderly were making regular use of them. Public toilets are neither ephemeral, nor something we need to “overcome”. In fact, I’m increasingly of the opinion that “developed” (Level 4) nations have far fewer public toilets than are actually required.

Juxtapose: The Useless “Army Area”

India, thankfully, is not a terribly violent nation. Bangalore has little use for the army any longer and it seems quite bizarre to use valuable inner-city land for military training exercises. Yet a substantial portion of the city can be seen on Google Maps as large, blank and grey: labelled “Army Area”. The cadets can be seen early in the morning… running around in uniform or calling out strokes in a rowboat on Ulsoor lake. They seem… bored.

Disaster Relief: Never mind the army of 2030, the army (and navy, and airforce, and whatever other antiquated units of government you can think of) of today should serve one purpose: global safety and security. At a minimum, the military and military resources, such as land, could slowly be funnelled into government departments of greater utility, such as DART, serving all of India, at a bare minimum — and hopefully its neighbours. I’m sure there is debate to be had as to whether starvation and poor health of one’s own citizens is a “disaster.” Some of us might choose stronger words. But as long as I’m fantasizing, a Bangalore of 2030 would welcome its least fortunate citizens into refurbished Army Areas to serve simple meals and provide basic healthcare services.

Juxtapose: Lost Trees

Bangalore’s old tagline of “The Garden City” is less appropriate with each new building constructed. Parks remain, but Koramangala is unlikely to be returned to the earth within our lifetime. Those who knew the old Bangalore speak words of regret. Those who see infographics describing urban density wonder what can be done (other than the childish suggestion that immigrants should stop coming here).

Aggressive Reforestation: Inside and outside of Bangalore, an appreciation and understanding of the necessity of plant life is coming. (For some, it’s already here.) Augmenting the desire to maximize land usage, homes will one day be built smaller with space for trees and gardens. Rooftop gardens will fill the space not occupied by solar panels. Government-mandated green spaces in every neighbourhood will maintain some semblance of balance and reverse Bangalore’s transformation into an urban heat island. Self-awareness of one’s space consumption is unlikely to derive from the longing for parks; this change will require education and perseverance.

Juxtapose: Lost Religion

My generation is not violent and drug-addled due to its dearth of spirituality. A sagging of religious participation will not degrade our cities into dystopian hellholes. It has, however, lost some of the values and guidance religion provided our grandparents. Generosity is no longer to open one’s home to any who need it but to donate a tax-refundable amount to a charity of one’s liking. Forgiveness has lost a universal quality and favours a polar described by media on all scales, each running an attention deficit. Time my grandmothers dedicated to community and silence my peers dedicate to music and alcohol.

Space for Silence: Meditation, prayer, uninterrupted contemplation. These wildly different activities all carry the same characteristic: absolute silence. There are few spaces these days for anyone of any background to simply escape the din of Bangalore’s public space. Universally-accessible quiet spaces do not exist yet, which makes them in some ways more fantastic and futuristic than self-driving, all-electric robot cars. Despite this, I think Bangalore is capable of constructing a building where conversation and mobile phones are not permitted. 2030 will see some such space (even if I have to build it myself) but it is hard to say how common they will be.

Space for Generosity: The recent outpouring of support from the general public for those in need of help in the Chennai floods is proof that the average citizen wants to help and will do so when required. I often wonder how to make this a daily or weekly practice for myself, rather than one I hold for unpredictable catastrophe.

In 2030, Bangalore’s neediest will find space to sleep and poop — and simple meals to eat — without this assistance attached to any particular belief system. Nearest to this are the meals provided in Gurudwaras, but in time I expect to see spaces emerge for all of us who feel our free time could be spent more meaningfully.

Juxtapose: The Wealth Gap

Bangalore is not yet a rich city. It may never be one of the wealthiest cities on Earth. The wealth gap is widening and for many people (and many industries), resources will remain scarce. This is a wonderful constraint, thanks to its realism.

Focus on necessity: Bangalore is full of clinics, hospitals, and schools. Markets for the most necessary items are walking distance from any home and India is unlikely to form food deserts like the U.S. suffers from. A continued focus on absolute necessity for all income levels will ensure that as the Bangalore of 2030 starts to look like Olympus from Appleseed, one can still buy sitaphal from a wooden cart on the side of the road while it’s in season.

As Bangalore’s citizens’ access to personal transportation increases, clinics and hospitals risk suffering the centralization which has occurred in rural Canada. I don’t yet see this happening and I hope it does not. A healthy Bangalore of 2030 still has walking-distance health clinics in almost every neighbourhood.

Schools are another matter. It is possible that progress in remote learning will mean “homeschooling” can take on a different definition, schools may be more about physical space than about colocation of teachers and students, and the trucking of children from one end of the city to the other will become a goofy story about industrial-age lifestyles for the next generation to laugh at.

Tiny houses: While hinting at my hippie granola upbringings and preferences, limited resources should push more and more people back toward sensible living accommodations — even the rich. Bangalore draws its cultural inspiration from the subcontinent’s long history and mixes it with ideas from around the globe. The U.S. and its predominantly overindulgent lifestyle features heavily, but that can be balanced by the sensibilities of Osaka, Sao Paulo, and Seoul. The Tiny House Movement may very well fade away as an extremist fad, but some variation thereof could become the norm for a progressive Bangalore.

Repeatability, Repeatability, Repeatability

More valuable than any other item on this list is the ability of the rest of the world to repeat Bangalore’s actions from the coming 15 years — and for Bangalore itself to repeat and refine these actions into 2045. Repeatability is hard to capture in a painting, but at its core is no doubt simplicity, which I think can be expressed artistically, even when describing an array of concepts. Indeed, the desire to see such artwork is a desire to witness these ideas expressed as simply as possible, so that anyone can understand and appreciate them.

Bangalore represents the breadth of the global economy, from the untraveled and uneducated to the owners of multinational corporations. It is a meeting ground for people of all fields and it’s the perfect laboratory to run experiments predicting the global society of the future.

This is essential. The infrastructure and lifestyles of Earth’s wealthiest nations are not sustainable and not repeatable. As the global economy continues to flatten itself, the behaviour of the wealthiest will need to change, from London to Los Angeles. Comparatively, the infrastructure of the Earth’s poorest nations will continue to heal and mature. As every nation frees itself from conflict, it will require the tools to become a modern economy as quickly and cheaply as possible.

Bangalore 2030 is a blueprint.

Essay originally published on Hungry, Horny, Sleepy, Curious. (2015).